Air quality is not normally one of the metrics taken into account by planners, architects, and developers when deciding what to build and where to build it but it should be. Knowing what the air quality is at a certain location at a certain time and being able to relate that to human activities, both in the immediate vicinity and farther afield, is important information. This is especially true when considering the health and well being of the most vulnerable among us - young children - who are all too frequently overlooked by those who maintain and improve the built environment of our cities.

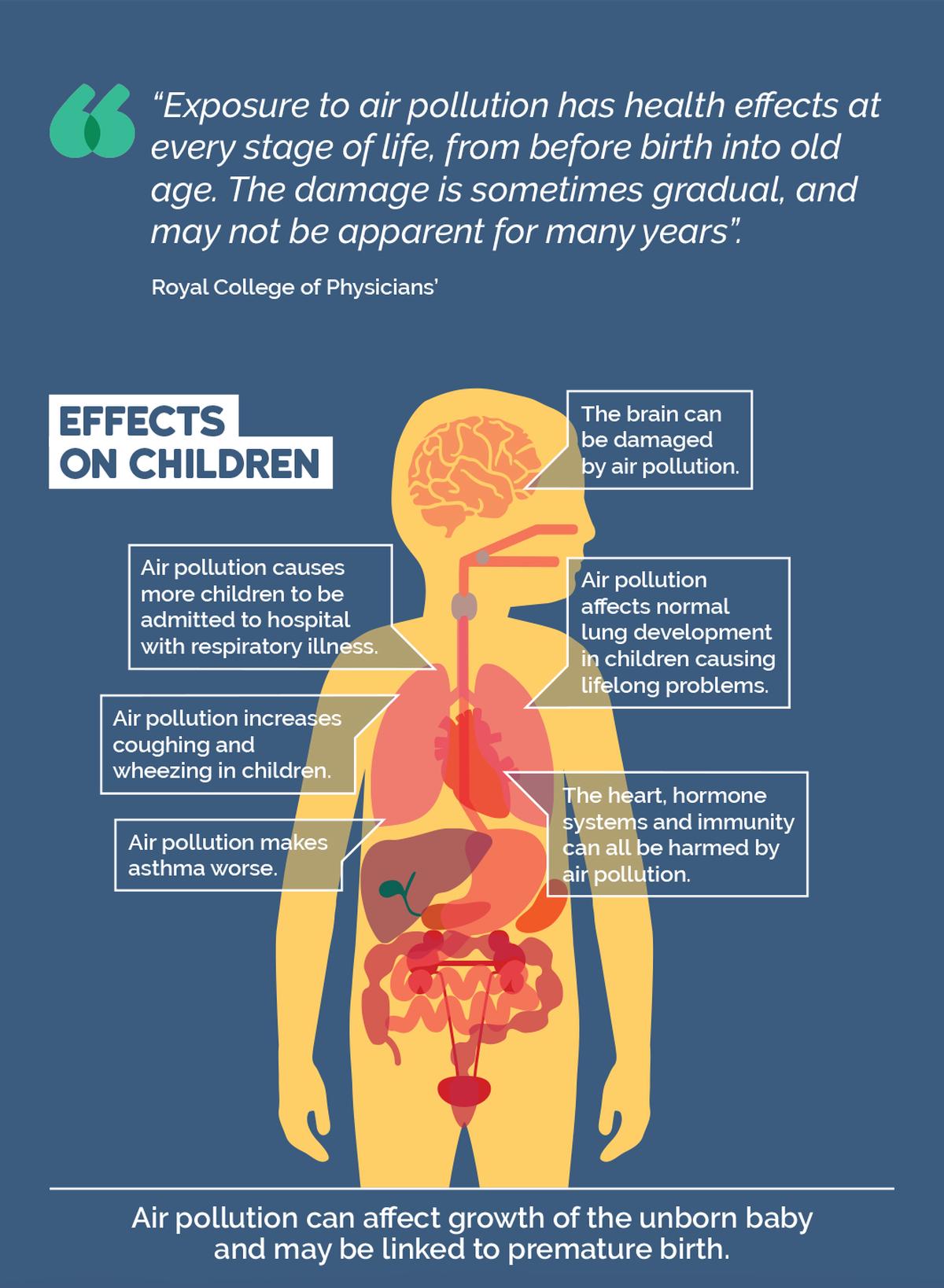

Globally, one in ten deaths in children younger than five is attributable to air pollution. Children are particularly vulnerable to air pollution because they breathe up to four times faster than adults, thereby absorbing more pollution, and their brains and bodies are still developing. Making matters worse, air pollutant concentrations can actually be higher closer to the ground where young children breathe.

While the path to remaking our cities to promote the health of children is winding and complicated, there are two straightforward directives that can help guide us. First, reduce exposure to air pollution where young children spend time and invite young children and their caregivers to spend time where air quality is better. Second, empower marginalized communities most impacted by poor air quality by building their capacity to collect and interpret air quality data, educate young people and adults on the health impacts of exposure to dirty air, and make room for them at the decision-making table.

In Copenhagen, Gehl piloted an approach driven by the first directive that was informed by an assessment of how streets, childcare institutions, and public spaces are laid out combined with careful observation of who is occupying and traveling through these spaces and what they are doing. Cross-referencing this information with hyperlocal air quality data collected by Google Street View cars, Gehl was able to identify where and when children and their caregivers were most exposed to air pollution and suggest street design interventions - removal of on-street parking, establishing vegetated buffers between the roadway and the sidewalk, and traffic calming measures among others - that would reduce air pollution concentrations where exposures for children and caregivers was likely to be highest. In addition, “cleaner air route” signage was introduced that directed pedestrians to secondary roads with less traffic congestion and seating was introduced mid-block to invite children and their caregivers to commute and spend time in areas with less air pollution.

While Gehl’s approach to the first directive is undoubtedly effective at reducing air pollution exposures for children and their caregivers, the first directive is not sufficient when used in isolation from the second. Inequities in access to clean air are the result of inequities in access to political power, so a purely technocratic approach to addressing the problem does not get at the root cause. That is to say, you can redesign the urban environment to nudge people away from air pollution, but this does little to reduce pollution from sources nor address inequitable exposures to air pollution across cities and between regions. Driving this kind of systemic change requires that the marginalized communities most impacted by air pollution be in the driver’s seat; that they have sovereignty over the air quality data collected and access to the resources and actor networks required to translate their findings into action.

In concrete terms, acting within the letter and spirit of the second directive means community based organizations that legitimately represent the interests of their communities should:

- decide which organizations or companies to work with in designing and executing air monitoring campaigns/networks;

- receive funding to oversee and coordinate work with all selected contractors;

- receive funding to conduct public outreach and run related educational programs for young people and public facing programs for adults;

- are empowered to author or substantially contribute to any project communications or reports and receive funding to do this; and

- receive a commitment from policy makers and regulators to develop mechanisms that can translate their findings and solutions into policy prescriptions and effective regulations that are vigorously enforced.

In the Bronx and Brooklyn, the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance’s Community Air Monitoring Project for Environmental Justice is a model for how environmental monitoring should be conducted. The New York City Environmental Justice Alliance and their community-based partners led every facet of the project from study design to final report and are now actively working with the City and State of New York to decide how additional air surveillance work should be conducted and looking to advance interventions and strategies that will reduce pollution from sources concentrated in low-income communities and communities of color.

Ultimately, reducing air pollution exposures for children and their caregivers is dependent on a transformation, not just in how governments build - directive one - but in how they operate - directive two. We need to see children and their caregivers not as agents to be acted upon, but as agents in their own right who are embedded in communities that have been acting for decades, if not centuries, to overcome the deficits in their quality of life versus more privileged citizens. Communities whose struggles for equality are the foundation from which our conception of inalienable human rights have arisen, including the right to breathe clean air.

Image Credit: letscleartheairliverpool.co.uk/what-is-air-pollution/

Get AirBeam

Get AirBeam